- Feast countdown = 36

- Current craving = Nothing. I gave myself a stomach ache earlier with too much Lucky Charms.

- Current craving distraction = My stomach ache

My brain is mush tonight and my stomach is angry, so this post will be short and sweet. My oldest sister Beth sent me to NPR's Speaking of Faith blog yesterday, where they wrote about Swedish parental leave for fathers. Beth has two kids under the age of 3, so you can see why this would be pretty interesting for her.

It also piggybacks on a post I wrote a while ago on men breastfeeding. Yes, the controversial one :) Even if I don't agree with everything in Sweden's policy, I do love the idea of mothers and fathers deciding together on the amount of leave they will each take. It empowers and encourages fathers so much more in the process. See what you think...

Sweden’s “Daddy Leave”

Nancy Rosenbaum, associate producer

“Now men can have it all — a successful career and being a responsible daddy.”

—Birgitta Ohlsson, Sweden’s Minister of EU-Affairs and a mother-to-be

In Sweden, state financial incentives are changing the face of modern fatherhood. According to the International Herald Tribune, Swedish families receive 13 months of government-subsidized parental leave. Dads get two months and so do moms. Parents can divide up the remainder however they choose. But here’s the kicker: if fathers don’t avail themselves of their “daddy leave,” then the family loses out on a month of paid subsidy.

In Sweden, state financial incentives are changing the face of modern fatherhood. According to the International Herald Tribune, Swedish families receive 13 months of government-subsidized parental leave. Dads get two months and so do moms. Parents can divide up the remainder however they choose. But here’s the kicker: if fathers don’t avail themselves of their “daddy leave,” then the family loses out on a month of paid subsidy.Apparently in Sweden, daddy day care is the new normal. It’s an interesting example of social policy influencing human behavior and perceptions of masculinity. According to data from the Swedish Social Security office, Swedish fathers whose children were born in 2002 used an average of 84 days of paid paternity leave. That’s an increase from 57 days taken in 1999.

How does Sweden’s policies compare to other countries around the globe? For one perspective, check out these global parental leave maps created with Wikipedia data by an American dad/blogger living in Sweden (while on his daddy leave no less).

As I observe so many of my friends and colleagues grappling with work-life balance, it’s interesting to learn how other countries and cultures are approaching these parenting challenges, and how notions of what it means to be a man are shifting in the process. I’m also reminded of a story about what gets lost when fathers stay at the sidelines of child rearing from our show with Rabbi Sandy Sasso:

“I remember a father telling me that he doesn’t usually read to his children at night, that his wife did, the mother did. But one night, he read, and he decided to read this book. And he decided to leave out the questions, because he felt that would take too long and it would be too long a bedtime ritual…And the child stopped him in the middle and said, ‘No, Dad, ask the questions. Ask the questions. I want to talk.’ What she wanted to do is have a conversation in this quiet time when nothing else was intruding on their lives.”

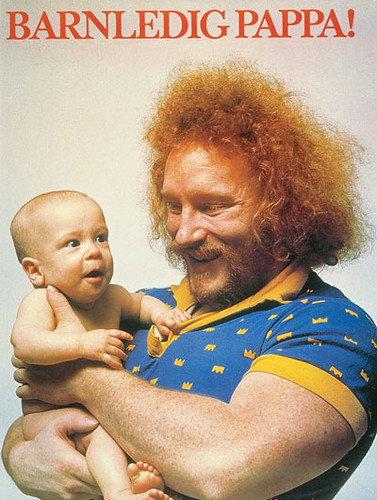

In the image above, Swedish weightlifter Hoa-Hoa Dahlgren featured in a 1970s ad produced by Försäkringskassan — the Swedish Social Insurance Agency — to encourage fathers to participate in paid paternity leave. (photo: Reio Rüster)